UK’s mad energy policy is a potent deterrent to foreign investors

By Simon French, Chief Economist and Head of Research

Conducting economic policy in a time of war - both a military one, and a mercantile one - is a huge challenge for any government. Ideological tenets that were forged in opposition, and at a time of near-zero interest rates, get ditched. They are replaced by pragmatism out of necessity. This has been the experience of Labour since they came to power last July.

In opposition, Labour could flirt with the magic money tree and Modern Monetary Theory. In government the global bond markets have demanded adherence to fiscal discipline. In opposition, Labour could lionize the international aid budget. In government they have cut that budget further to fund the UK’s creaking defences. In opposition, downbeat commentary about the UK economy and criticism of the US President were irrelevant. In government such comments have consequences.

Political activists to the left of the Labour Party see this pragmatism as a strategic misstep, and a betrayal. Their argument goes that it exposes the lack of a differentiating economic vision from Conservative party, and is a gift to Reform. Investors in the UK see pragmatism as an attractive trait amidst an increasingly unstable world order. The Prime Minister and Chancellor deserve credit for their approach. The question now being posed is how far does such pragmatism extend?

In particular, one policy comes up again and again in meetings I have with investors that are looking to put capital to work in the UK. That policy is the UK’s approach to energy security.

It is hard to overstate quite how mad the UK’s energy policy looks to outsiders. Investors are scrambling to redirect their capital into other countries after years of over allocating to the United States. This is a generational opportunity for a UK economy that has run a investment-light model for forty years. And yet when marketing the UK as an investment destination, many investors struggle to square the government’s primary mission for economic growth with a penal 78% tax rate on energy profits, and a commitment to no new licences for the UK’s North Sea Continental Shelf. That approach looks like an irrational own goal. It is an impediment to economic growth and prosperity that is hiding in plain sight.

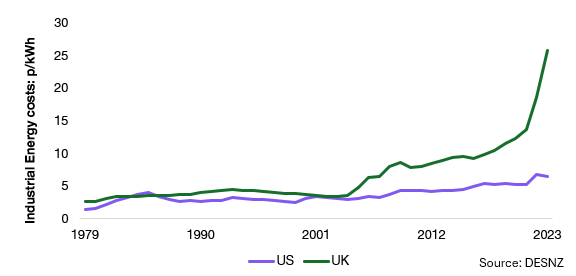

Let’s put some data to this. Data that is readily available to investors taking a fresh look at the UK economy after a long hiatus. The latest information released by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero suggests that UK industrial energy costs, after tax, stood at 26p/kWH. This is - by some distance - the highest across the EU and the G7. In the US this equivalent rate is just 6.5p/kWH. Twenty years ago, these prices were the same on both sides of the Atlantic.

Share

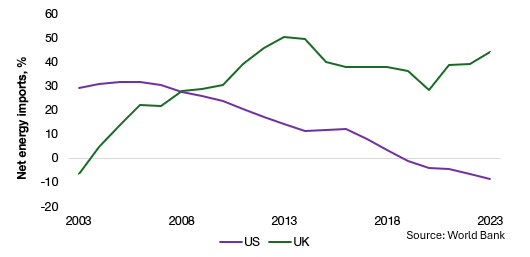

Over this same twenty-year period the UK has moved from being a net exporter of energy, to importing more than 40% of its energy needs. The UK’s energy market has become reliant on events outside its direct control. By contrast the US has gone on exactly the opposite journey. Having imported a peak 32% of its energy needs as recently as 2004, it is now a net exporter. The inverse symmetry of these two trends is nothing short of remarkable.

Two countries, whose economic growth paths - for good and for ill - have tracked these energy market trends. This is not solely a story of old economy, and heavy industry. Energy-hungry technology companies will increasingly gravitate towards low-cost energy markets. Microsoft, Google and Amazon have all recently signed contractual terms with the US nuclear industry such is their conviction on the need for power demand for data centers, and AI processing capacity. It turns out that the intangible economy has very tangible needs and wants.

There are two aspects to the hiatus on North Sea exploration that appear deeply irrational to investors.

The first of these is emissions. Investors fully recognise the global imperative to decarbonise, however in reducing domestic supply of oil and gas the UK is, in fact, adding to carbon its energy mix. It does this by increasing its reliance on dirtier foreign imports. Approximately a third of the UK’s gas demand currently comes from imported Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) from the US and Qatar. At 79kg of carbon per barrel of oil equivalent (boe) this has almost four times the carbon intensity of UK production at just 21kg/boe. The processes of liquefaction and transportation across the seas are both carbon-intensive. A straight replacement of imported LNG by domestic supply would diminish the UK’s total carbon footprint, and reduce the offshoring of UK emissions.

The second irrationality is the perverse fiscal implications of limiting North Sea exploration at a time of tight public finances. Reduced domestic production raises decommissioning charges for taxpayers - estimated at £24bn over the next decade - and reduces Treasury tax revenues. The Laffer curve – where a hypothetical cut in the tax rate generates more in tax revenue - is often cited in UK economic discourse with little empirical support. But at 78% - the current marginal tax rate on North Sea energy profits - we are in clear Laffer territory. At a time when the government is facing fiendishly difficult decisions on public spending and tax, leaving tax revenue on the table is an odd approach, to put it mildly.

Despite the UK government recently launching a consultation on the future for the Energy Profits Levy beyond 2030, the Chancellor’s leadership of the growth mission and sound public finances will have a hollow ring if that tax persists in its current guise beyond the Autumn Budget.

There is a final impact on the public finances that is most maddening of all. The UK public balance sheet will not have been short of requests in the current Spending Review. From schools to roads. From prisons to hospitals. There are arenas where public capital is essential to plug clear market failures, and underinvestment. But energy is not one of these failures. The private sector is highly proficient at funding all parts of the energy market from generation, through transmission, to storage. The very real risk is that the Spending Review spreads scarce capital budgets too thinly. The funding for Great British Energy looks like an unnecessary fiscal folly.

Permissioning private investment and reinstating a tax rate that incentivizes domestic energy production would be a highly symbolic sign of pragmatism in a dangerous and volatile world. It would also send the strongest possible signal that the UK government is credible about economic growth.