To help growth, we need to celebrate our leaders doing nothing

By Simon French, Chief Economist and Head of Research

Wednesday’s Spring Statement will be a test of the UK government’s nerve. Headlines will highlight a halving of this year’s economic growth rate, and announce the return of austerity. Attacks from all sides of the political aisle will abound. From the left will be calls for new wealth taxes despite the UK tax take being at an eighty-year high. From the right will be calls for a smaller state despite signs of core public services creaking under their existing funding levels. The middle may just sigh and wonder how the UK escapes what looks like a fiscal doom loop.

How did the nation’s finances get here just five months on from a Budget that was supposed to be “clearing event”, and one that drew a line under the instability that has dogged UK economic governance in recent years? The first thing to note is that the difficulties faced by Chancellor Rachel Reeves are not all of her own making. Higher interest rates since July’s General Election have been a global phenomenon. Reeves will be at pains to make this point this week. The interest rate for the UK government to borrow for ten years is up by 0.4% since July, the same amount as for the German and French governments, whilst in Japan that interest rate has risen by 0.5% - albeit from a much lower level. Only in the US - courtesy of recent concerns over the health of the American economy - have debt interest rates fallen back.

The same global context is also relevant to the UK growth downgrade that is inevitably coming from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). The OBR’s estimate for economic growth is set to be reduced to just 1% for 2025, down from an enthusiatic 2% forecast back in October. The OECD last week produced its latest growth forecasts for all G20 economies that widely marked down economic growth projections for 2025 on the back of concerns over trade fragmentation. Despite avoiding the worst of President Trump’s tariff threats so far it is inconceivable that a mid-sized open economy like the UK won’t get caught up in the crossfire.

However, any balanced assessment of how we arrived at this position of lower growth and higher debt interest will also point to domestic missteps by the Labour government. The choice of a £25bn/year increase to employer national insurance as the vehicle to plug the public finances has caused a sharp slowdown in hiring. Payroll employment has now flatlined since last year’s General Election, and recruiter surveys point to more softness in the jobs market as the National Insurance changes come into force next month. Attempting to tap employers for revenue at a time when the National Living Wages is rising at more than twice the rate of inflation, and firms are absorbing the £5bn impact of a wide-ranging Employment Rights Bill, always risked economic indigestion. Income tax increases or a reverse in Jeremy Hunt’s employee national insurance cuts would have been less damaging, if politically harder, approach.

That misjudgement was aplified by the negative tone surrounding the economic inheritence that was employed last summer. This sapped household and business confidence which had been riding at multi-year highs. This spoke to the naivity of government ministers with no experience of high office, and scant experience of the private sector. Lower consumer spending and investment has been the direct result. The government has u-turned too late to regain the animal spirits that could have made a difficult fiscal inheritance, a little easier.

The test coming out of the Spring Statement will be whether what government insiders are describing as a “minor fiscal event” this week triggers a change of economic direction ahead of the major fiscal event, the Budget, later in the year. £5bn a year of welfare savings and Civil Serviuce administration savings of 15% by the end of the decade - whilst politically difficult for Labour - are sticking plasters that buy a bit of breathing room over the summer. The hope is for better economic weather and for some of the government’s much-vaunted supply side reforms on planning and capital investment to start bearing fruit by the autumn.

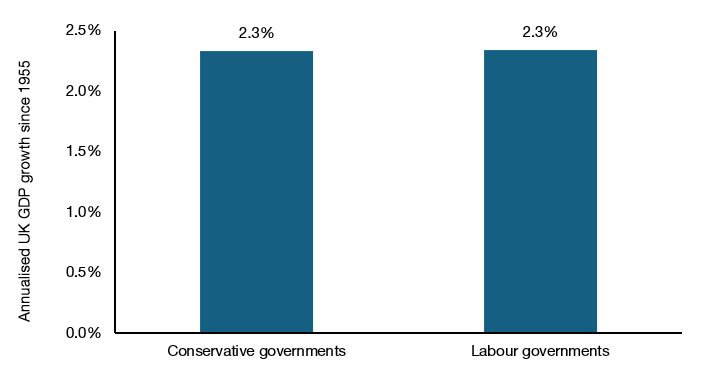

There will be plenty of voices that will claim to have already seen enough. However those ready to deliver an irreversibly damning verdict on the government’s economic plans would do well to recall the 364 economists who wrote to Margaret Thatcher in 1981 warning her she was dangerously off beam. The next seven years following that letter saw UK per capita GDP grow at an eyewatering 3.5% - more than twice its long-term average. Before Times readers spill their coffee in protestation at the very different economic doctrines of Thatcher and Reeves it is worth noting that economic growth under both Labour and Conservative governments has been identical since the Second World War at exactly 2.3% a year. Anyone who argues that one party has the monopoly on economic growth reveals they know more about politics than about economics.

So what can the government do to avoid another fiscal squeeze later in the year, and each year thereafter? A squeeze that will continue as the UK population steadily ages over the coming decades? Much of the debate correctly surrounds increasing productivity, using new digital tools, and reducing the practical barriers and cost to getting capital deployed.

However my experience of a decade in the Civil Service and now a decade in the City of London suggests to me there is something more fundamental for public service leaders and ministers - the skill of stopping doing things. In the City the best investors are not those who are good at buying stocks and bonds, they are the ones who are good at selling them. I will venture that the best ministers and public service leaders of the future will be those who identify what not to continue doing, rather than identify new intiatives to embark upon. The alternative to this is a lot of mediocre, underfunded public bodies.

The good news is that the recently announced abolition of NHS England suggests this mindset does exists in pockets. But it is not wholesale, or cultural. The government continues down the path of wanting to create a football regulator. There is no culture of celebrating any decision to do nothing, even where it means simply getting out of the way of a hugely profitable and succesful UK export. If Chancellor Reeves and her successors wants to avoid further difficult fiscal events then working out what to do less of is really the only option.