Thought of the Week – The geopolitics of the energy transition: Are fossil fuels more secure?

I have written earlier in the year about the challenge the energy transition faces in terms of geopolitical dependency. Many of the metals we need to build windmills, energy storage facilities, EVs, etc. are coming from a handful of countries. And let’s face it, these countries are typically not very stable or particularly friendly to European and North American importers. But have we thought about comparing these geopolitical dependencies to our dependencies in fossil fuels?

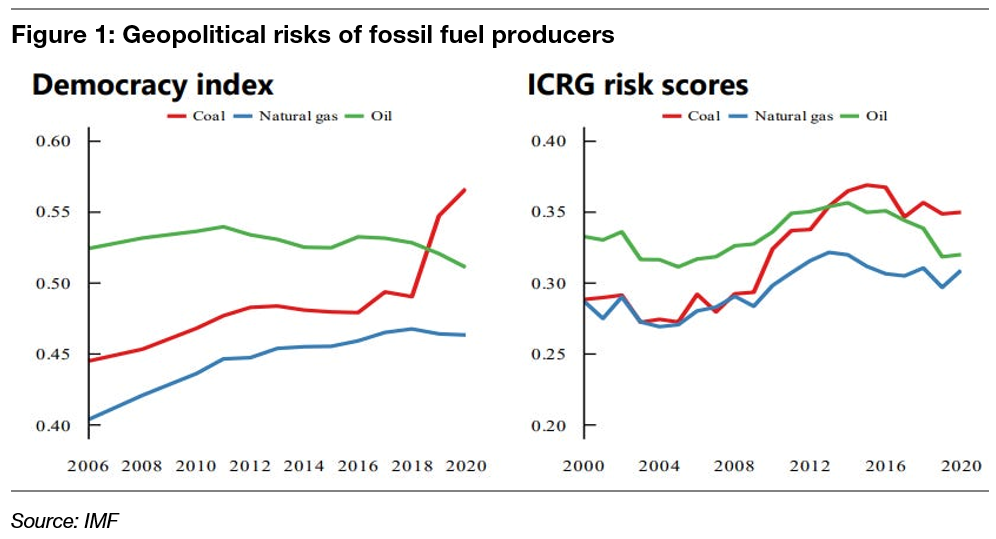

The IMF recently published an analysis of the geopolitical risks in fossil fuel consumption. To start, they looked at the political and country risks in the countries that produce coal, natural gas, and crude oil. The figure below shows how these risks have changed over time. The left-hand chart shows country risks measured by the democracy index, with higher values indicating less democratic and more autocratic regimes. The right-hand chart shows country risks measured by the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) which takes into account political stability, socioeconomic conditions and internal and external conflicts. Again, higher values indicate higher risks.

Clearly, the risks in natural gas and coal imports have increased while the risks in oil imports have declined. The declining risk in oil production is due mostly to the increase in oil production and oil exports from the United States, while the increase in risks in natural gas production are due to the rising importance of producers in the Middle East (mostly Qatar and Iran). Meanwhile, risks in coal production have increased dramatically because high-cost producers like the US have increasingly withdrawn from the market, leaving behind countries like Australia, China, and Indonesia as major producers of coal.

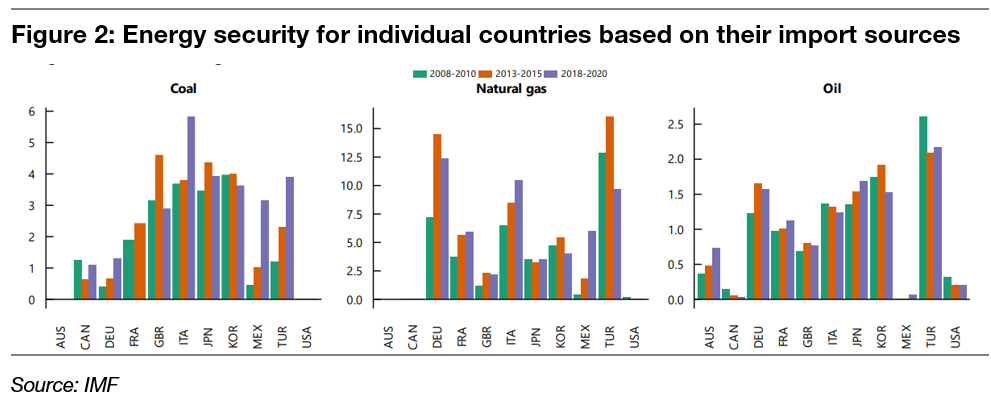

But the risks shown in figure 1 are global averages. Yet, countries like the US or Australia don’t import coal because they have their own domestic supplies. So, how does the geopolitical risk look like for different countries? The figure below provides an answer for the major industrial countries.

The United States, Canada and Australia are truly the lucky countries because they have their own supply of fossil fuels and very little import dependence. For them, transitioning to renewables doesn’t reduce geopolitical dependency but may increase it. But for the rest of the developed world, transitioning to renewables not only makes sense economically and from a climate risk point of view. It also reduces geopolitical dependencies.

Yes, transitioning to renewables increases the dependency on transition metals, but this dependency declines naturally over time for two reasons.

First, as technology advances, we are using less and less of these critical metals. We now have batteries for EVs that do not use any cobalt (see here, here, and here, for example) and these batteries will increasingly replace the current battery technology that relies heavily on the metal.

Second, our dependency on these transition metals will drop naturally as we build our network of wind and solar farms as well as energy storage facilities. Once the renewable energy infrastructure is in place, we don’t need new metal supplies to run it. Our dependency on fossil fuels is permanent. If we can’t get natural gas from Russia, we no longer can produce electricity. But if we can’t get any nickel or cobalt, the existing wind farms will still produce electricity for the rest of their useful life. And once these wind farms reach the end of their useful life, we can recycle the metals contained in them. This is why these transition metals are called ‘transition metals’ and not ‘renewable energy metals’. We are dependent on them during the energy transition but not once the transition has taken place. And this makes the transition to renewables a very interesting proposition for importers of fossil fuels because in the long run, it leads to lower geopolitical risks.

Thought of the Day features investment-related and economics-related musings that don’t necessarily have anything to do with current markets. They are designed to take a step back and think about the world a little bit differently. Feel free to share these thoughts with your colleagues whenever you find them interesting. If you have colleagues who would like to receive this publication please ask them to send an email to [email protected]. This publication is free for everyone