Thought of the Week - Hiring lotteries

Every so often, you read about yet another experiment where monkeys were used to pick stocks for a portfolio and that portfolio outperformed the ones selected by professional investors. I wrote about such an experiment in jest a couple of months ago. But as is now widely known, simple equal-weighted portfolios with random assets tend to outperform more sophisticated ‘optimised portfolios’. The reason behind this phenomenon is that in practice, it is very, very hard to forecast which stock is going to outperform other stocks in the same industry, region or market overall. There are some indications we can get from analysing a stock that allow us to shift the odds in our favour, but truth be told, the uncertainty around any kind of stock market prediction is so large that in practice the odds shift very little if at all.

But let’s assume that through your analysis, you, dear investor, are able to avoid the absolute duds in the stock market. Most likely, if you can do that, you are still stuck with hundreds or even thousands of stocks globally that all have some decent prospects for growth and high returns. But hardly any of us can invest in thousands of stocks (unless they simply buy a market ETF), and we want to narrow it down to a handful of the most promising stocks in our portfolio. Once you have eliminated all the obvious outliers, wouldn’t it be a good idea to just select your stocks at random from the remainder? The data on stock selection would support that process, but then again, the problem for many investors would be to justify such a seemingly careless course of action.

But now think about a company trying to hire a new top-level executive. Or you trying to hire a new member of your team. Obviously, we are going to select candidates with the best qualifications, some of which – like academic qualifications or a track record as a portfolio manager – may be measurable. But most of the qualifications needed for the jobs in today’s knowledge economy will be softer. Things like emotional intelligence, the ability to work in teams and think outside the box are hard, if not impossible to measure in an interview process. This is why the overwhelming majority of people are incapable of identifying the best candidate and why job interviews lead to terrible outcomes.

Enter Chengwei Liu who has made a radical suggestion: In some circumstances, it might be best if a company selects people based on a lottery. He argues that when companies hire senior executives, the hiring managers tend to hire people that are like them. This is a well-known tendency of all of us. When we can’t decide which one of several individuals is going to perform best at a task, we tend to look for similarities to our own strengths and weaknesses. And because we are obviously successful at our jobs, the person with the most similarities to us is most likely to succeed at the task. The result is that we all have an innate tendency to hire people like

us.

But when it comes to successfully completing complex tasks (whether it is running a business or other tasks) there is a proven benefit to selecting more diverse teams. And I am not talking about ethnic or gender diversity here, but cognitive diversity. Teams of people with a wide range of thinking and problem-solving modes perform better at complex tasks than teams of people who all think more or less alike.

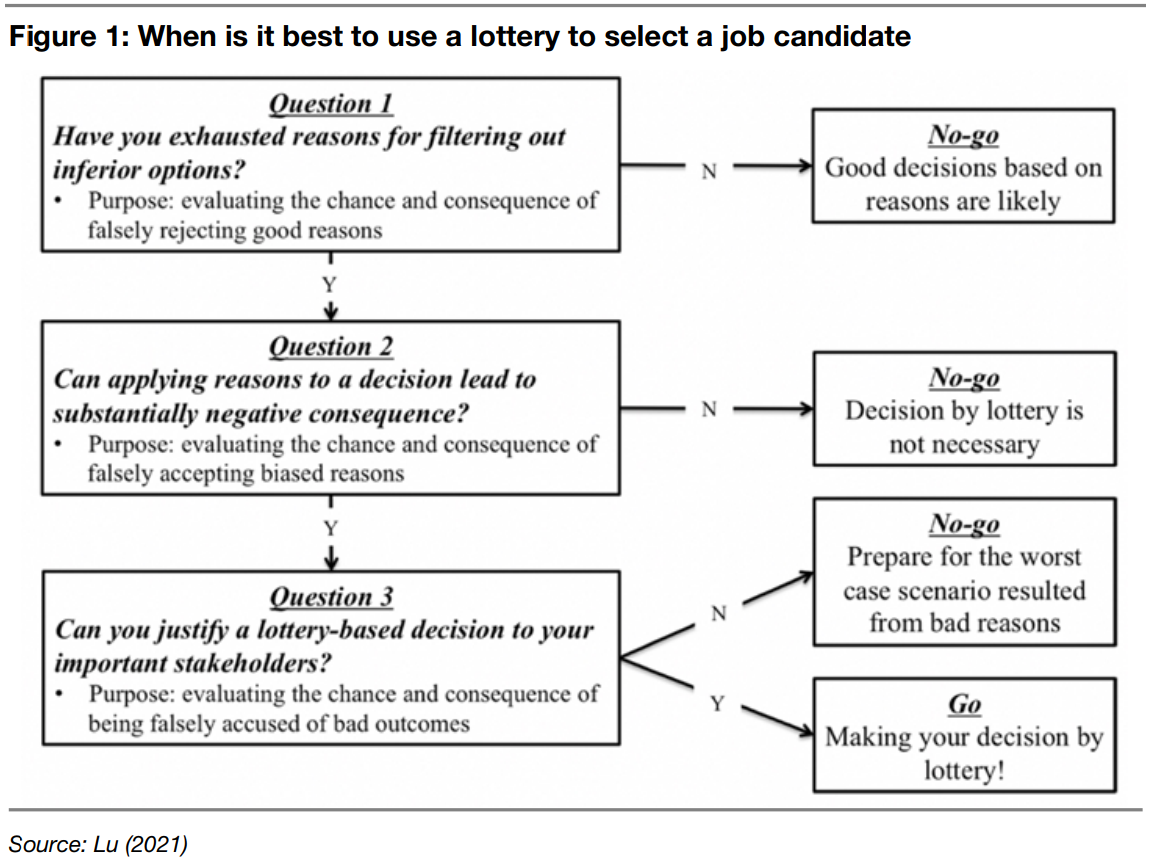

To benefit from this diversity bonus and break through our innate tendency to hire people like us, Liu suggests a simple process like the one shown below. Basically, it boils down to first eliminating the inferior candidates by looking at their skills and qualifications. Once the obviously unqualified candidates have been eliminated, one has to ask if there is a risk of making the selection worse by focussing on smaller and smaller details of the candidates’ profiles or using selection criteria that are not predictive of job performance. If that is the case, then it is best to select the candidate via a lottery.

That is, of course, if one can justify to one’s stakeholders (i.e. the boss) the selection process if the randomly chosen candidate is a dud and underperforms. And this is unfortunately the crux of the matter. Because selecting candidates via lottery (just like selecting stocks via a lottery) is so unconventional and so radical, there better be no mistakes. Because every mistake will immediately be interpreted as you not having done your job – even though, technically, you have done a better job than most people.

We observe this phenomenon so often in real life. Statistically, it may be better to do nothing or select via a lottery, but most people are not being judged by the long-term average success rate of their choices but by each individual outcome. And if only one of these outcomes is negative (which will happen almost certainly) you will no longer be able to continue your career. This is why goalkeepers in football (soccer) jump into the corner of the goals at a penalty, even though statistically it is better to just stand still and wait until you see where the ball is going. This is why fund managers continue to select stocks based on extremely minor differences in the fundamentals of a company even though a random equal-weighted portfolio would perform better in the long run. And this is why we continue to select people based on interviews rather than lotteries even though the organisation overall would benefit more from a lottery.

Thought of the Week features investment-related and economics-related musings that don’t necessarily have anything to do with current markets. They are designed to take a step back and think about the world a little bit differently. Feel free to share these thoughts with your colleagues whenever you find them interesting. If you have colleagues who would like to receive this publication please ask them to send an email to [email protected]. This publication is free for everyone.