Thought of the Week – The roots of deglobalisation

I believe that heightened tensions with China and the supply chain disruptions of recent years will not lead to a period of deglobalisation. Rather, I think most companies will diversify their supply chains to reduce dependencies and become more resilient. However, this view is being challenged by an analysis of the motivation behind recent government actions to benefit local industries.

Since the 1980s, industrial policy has gained a bad reputation as the government picking winners and causing regulatory interference in free markets. The picture is much more complex than that and I have written an in-depth analysis about this, but unfortunately, that is behind a paywall, so all I can do here is refer readers to an excellent review article by Réka Juhász, Nathan Lane, and Dani Rodrik.

But nevermind the details or what you or I think about industrial policies, the fact is that industrial policies are on the rise. The current resurgence started under President Trump, with his trade war with China, but was continued by President Biden with the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act. In Europe, we have the European Green Deal, and pretty soon we will see the introduction of the carbon border adjustment mechanism.

All of this goes to show that the push towards increased use of industrial policies and protection of local markets is driven primarily by industrial countries, not developing ones. The IMF is currently building a very detailed database of industrial policy measures around the world and has published its findings for the actions taken in 2023.

In 2023 alone, some 1,800 policies that distorted trade were introduced. Historically, about 70% of industrial policies are implemented by industrialised countries, but in truth, the actions are much more concentrated than that. About half of all industrial policy measures enacted last year were implemented in the US, the EU and China. The global free market is fragmenting into three hubs…

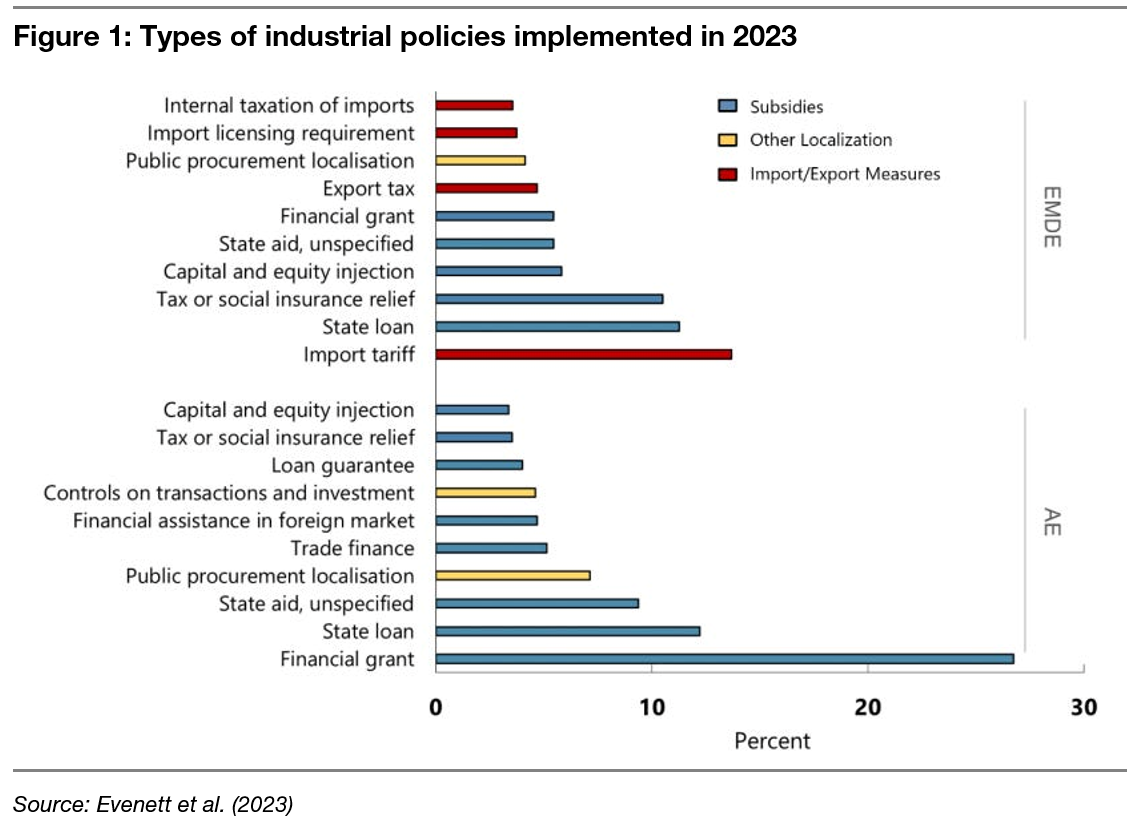

Another difference between industrialised countries and the rest of the world is the type of industrial policy used. In the industrialised world, trade barriers are not explicitly undermined like they are in developing countries that often resort to import tariffs or licencing requirements. Instead, industrialised countries rely on subsidies for different industries and companies.

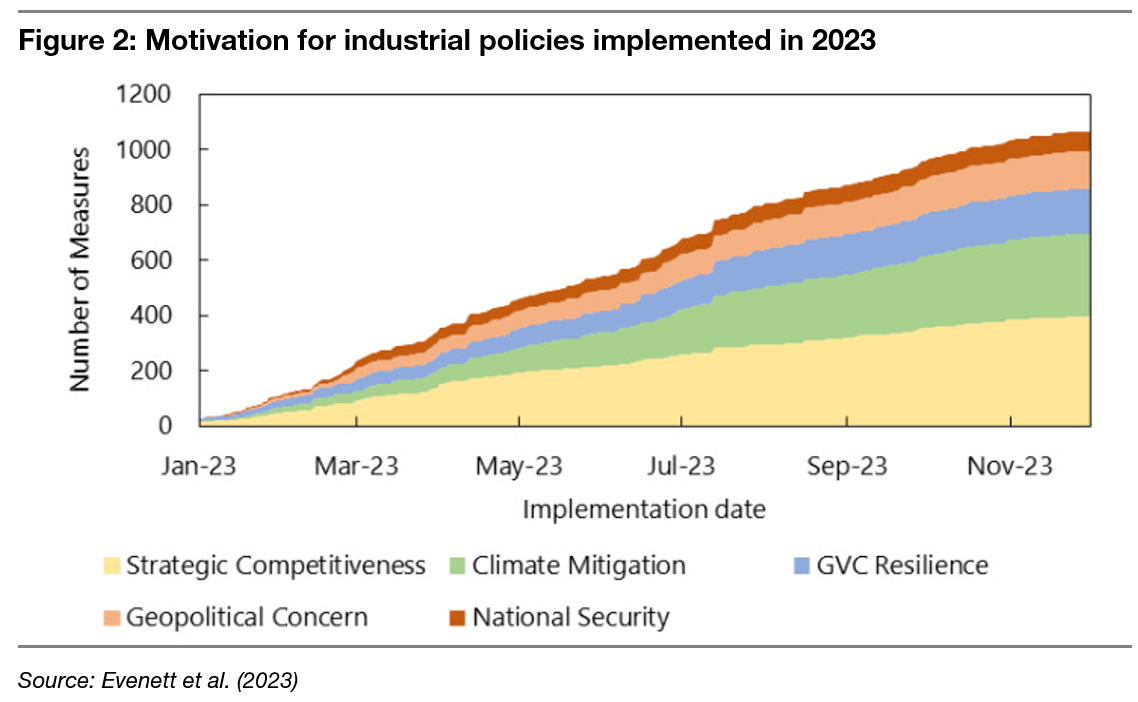

My initial reaction to this chart was that this simply shows that most of our industrial policies these days are focused on the energy transition and developing clean tech. But no – if one scans the motivations behind new industrial policy measures in 2023, climate change mitigation is only the second most common reason given. Most commonly, improving strategic competitiveness against foreign rivals is used to justify industrial policies. And if one adds geopolitical concerns and national security to the list, then 56.7% of all new industrial policy measures were politically motivated.

It isn’t the need to increase the resiliency of our global supply chains that drives deglobalisation. These measures account for only 15.2% of all industrial policies enacted in 2023. It isn’t the need to support the energy transition and develop and scale nascent technologies to fight climate change either (that’s 28.1%). By far the most important driver of the reversal of free trade seen in recent years is politics. And that is not about the government overregulating markets, it is the government pandering to its base and buying votes with taxpayer money.

Thought of the Day features investment-related and economics-related musings that don’t necessarily have anything to do with current markets. They are designed to take a step back and think about the world a little bit differently. Feel free to share these thoughts with your colleagues whenever you find them interesting. If you have colleagues who would like to receive this publication please ask them to send an email to [email protected]. This publication is free for everyone