Thought of the Week – A watershed moment for bond yields

By Joachim Klement, Head of Strategy

As I write this, we are emerging from a several-month period when 10-year government bond yields in the US, eurozone and the UK rose sharply despite central banks trying to cut interest rates. There are all kinds of drivers behind this development, like higher than expected inflation, stronger than expected jobs data and others. My missives aren’t about current market events, but rather designed to take a step back and look at the bigger picture, so let’s do that. How has the trend in long-term bond yields changed? And what does that say about government financing costs and long-term bond yields in the next couple of years?

Martin Ademmer and Jamie Rush from Bloomberg have done an exceptional job in modelling the trend in real 10-year bond yields over the last 50 years, and – crucially – disaggregating this trend change into different drivers. They built a large VAR model that covers 12 advanced economies and all drivers of long-term real bond yields that are typically discussed in markets and the academic literature:

- Trend GDP growth: Trend growth is mostly driven by productivity gains and changes in the labour force. Faster productivity growth increases the return on capital and thus the natural rate of interest, because government bonds have to compete with the higher returns available in equity markets and other asset classes. Similarly, if the labour force grows, more capital investments are needed to employ them, creating a greater demand for capital and thus pushing real bond yields higher to make government bonds more attractive relative to other investment opportunities.

- On the other hand, if the relative price of investment goods like computers and machinery declines, the need for capital investment drops as well, creating downward pressure on real bond yields.

- Demographic trends: As the population ages, the savings rate declines because pensioners save less than working-age people. As savings rates fall, the real rate of interest must rise to attract more investments.

- Income inequality works in the opposite direction of an aging society. Higher earners tend to save more, so rising inequality creates downward pressure on real bond yields.

- The global balance of supply and demand for safe assets. On the one hand, the government supply of safe assets has increased over time, but so has global demand for safe assets, particularly as emerging markets like China and India became wealthier. If the increase in demand outstrips the increase in supply, real bond yields drop and vice versa.

- Beyond this global balance of supply and demand, there is a separate effect from rising indebtedness of governments. As government debt piles mount, there is increased competition for domestic savings compared to other asset classes like stocks or corporate bonds. To attract the limited pool of domestic savings, real bond yields must rise if government deficits remain large.

- Changes in regulation for banks, pension funds, insurance companies, and others might create additional demand for government bonds, which reduces the real bond yield. This is expressed as a rising convenience yield, i.e. the premium paid for being able to hold safe and liquid assets like government bonds.

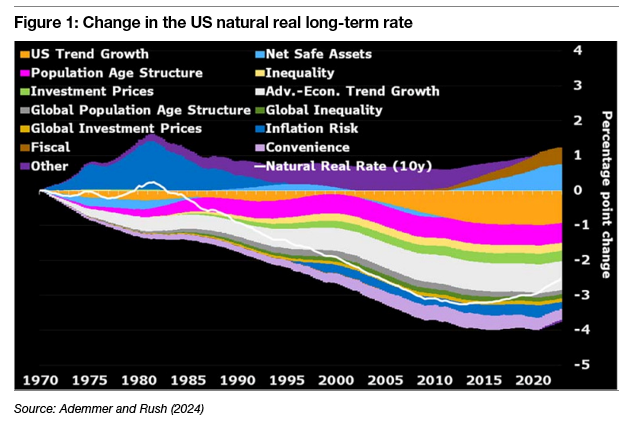

Taking all these factors into account, here is how the natural rate of interest has changed in the US (expressed are 10-year real government bond yields).

In the 1970s, the real bond yield was c. 5%, but it declined to less than 2% in the 2010s. The key driver for this decline in real bond yields was slowing trend growth both in the US and globally. The decline in trend growth in the US alone reduced the trend real bond yield by one percentage point. Another percentage point drop came from the global decline in trend growth.

The second most important factor driving trend real bond yields lower was demographic trends. The aging population structure in the US has reduced trend real bond yields by more than 0.6 percentage points since the 1970s. Globalisation, which reduced the costs of investment goods like machines and computers, cut trend real bond yields by another 30 basis points. In a sense, globalisation helped reduce our mortgage rates.

But most importantly, note that the trend real bond yield has started to increase again since 2015. There are two crucial factors driving this increase in real bond yield: rising government deficits and the shift in the global balance between supply and demand for safe assets. Both have pushed up real bond yields.

We are witnessing a watershed moment. For the first time in the last 50 years, we see evidence that bond markets are demanding a ‘risk premium’ for US Treasuries, because supply is outstripping demand.

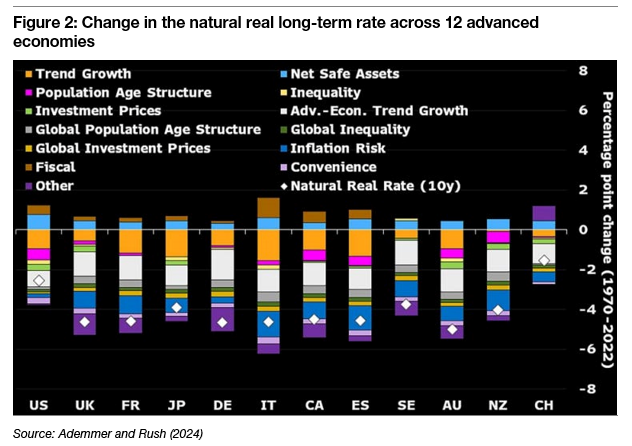

Crucially, this increase in trend real bond yields due to excessive government deficits is a global phenomenon. Here is the total change in trend real bond yields since 1970 across the 12 advanced economies covered in the study.

Note that the US suffered the second-largest increase in trend rates due to rising deficits and an oversupply of safe assets. Only Italy has seen a larger contribution from these two drivers. Meanwhile, Germany saw the smallest increase, though Australia and New Zealand have also done quite well.

I cannot stress enough how important these results are if confirmed by other independent research. Bond markets are starting to demand a rising risk premium to compensate for excessive deficits. These are thoroughly new developments, which didn’t arise until about 2015 to 2020, and they could change the entire dynamics of bond markets and government finances.

So far, there is no need to panic. After all, this is just one model and one piece of research. But add to that the other results we have seen in 2024 (see here), and you can see how the balance of evidence is tilting.

Thought of the Day features investment-related and economics-related musings that don’t necessarily have anything to do with current markets. They are designed to take a step back and think about the world a little bit differently. Feel free to share these thoughts with your colleagues whenever you find them interesting. If you have colleagues who would like to receive this publication please ask them to send an email to [email protected]. This publication is free for everyone